Posts Tagged ‘failure of economics’

Politicians, especially those in the USA and the UK, talk boldly about the creation of new jobs, growth and the increase of wealth as a result of their policies, and something similar is being heard right across the EU from Commissioners and MEPs through to national politicians. Their self-belief is ‘wonderful to behold’ but is it built on any firm foundation? There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that they have, essentially and dangerously, assumed that the future can be built using the out-dated policies and ideas of the past. Behavioural economist and business school professor, Alasdair White, argues that the future is based on the current trends and rather than simply assuming that current policies and theories will deliver the hoped for future, it is time for a serious re-think, it is time to look at the reality of the trends, and to conduct a thorough going review of policy. It is time for some serious soul-searching.

A brief history of work

Back in the 1980s, Peter Drucker, the management theorist, suggested that most work could be characterised as being one (or a mixture) of four types: labouring (making or moving things), craftwork (using special tools to make or move things), technical (using technology such as machines to achieve an orders-of-magnitude advance in the efficiency of making or moving things), and knowledge work (the creation of knowledge or the pure application of knowledge). Such a linear analysis may be too simplistic but it hints at what may now have become a significant issue: that the nature of the work being done, and thus the skills and knowledge to do it, may have changed in such a way that has not been fully recognised.

If we go back just over 300 years to the late 1600s, the majority of the workforce was engaged in agriculture, the work of which ranged from simple labouring to craftwork. The knowledge and skill sets required for the agricultural labourer were minimal, generally not requiring any formal education, with experience of the repetitious nature of the work filling any knowledge deficiency. For the craftwork of the period, such as blacksmithing, an apprenticeship to an existing craftsman served to provide the worker with the requisite practical knowledge and skills, but usually not the theoretical knowledge. This situation did not change much for the next 100 years, even though there were technical advances in the form of seed drills and other machinery that delivered orders-of-magnitude improvements in efficiency thus increasing agricultural revenue, both as a result of increasing yields and of reducing the number of labourers required to work the land as many were heading to the growing cities and the industrialised workforce.

In the early 1800s, Europe was subjected to continent-wide war that then spread to all parts of the globe as France with a varying collection of allies competed with Great Britain and its allies to control world trade. The outcome was the growth in demand for war materials such as weapons, ammunition and ships, with an accelerating shift in the labour force from agriculture to early-industrialised production of non-agricultural materials. Although this created the foundation of the industrial revolution and the urbanisation of the population, it didn’t change the nature of the work: it was still labouring, utilising a minimal knowledge and skill set.

This trend continued right the way through to 1940 when World War II massively increased the demand for production of war materials, to an extent that created an imbalance between supply and demand of labour and production capacity. The problem was resolved by the development of production techniques through the introduction of mechanisation but there was still little need for a more skilled or a more knowledgeable workforce. Even the shift in the 1950s to a consumerist economic model and the diversification away from large-scale goods towards small consumer goods did little to change the nature of the work being done: the majority was still labouring and doing craftwork, although increasing mechanisation was moving some sectors into a technical work categorisation.

Fitting the workforce for the work

Throughout all this, the education systems were meeting the demand for minimal knowledge and skills. The gentle upward trend for increased knowledge had seen the establishment in 1870 of compulsory education in the UK up to the age of 10; this increased to 11 in 1893 and to 13 in 1899. In 1914 the school leaving age in the UK rose to 14 and then in 1944 it was set at 15. It stayed at 15 for the next 28 years before rising to 16 in 1972 and has stayed there until today, although now a child in the UK has to either stay in full-time education until they are 18 or to take part in an apprenticeship or other authorised training that must last until they are at least 18 years old. Whichever way this is examined, it is clear that, at least in terms of public policy, a child is considered to have obtained all the knowledge it needs to be a useful member of the workforce and of society by the time it is 16 (or possibly 18).

But the correlation between the knowledge and skill sets required in the world of work and that provided by the education system has now been broken – and has been out of step for the last 30 years or more. However governments have yet to address this. Let me explain.

In the late 1970s and into the 1980s, as companies driven by the demands of shareholder value and shareholder ROI sought greater efficiency in their production systems, automation of routine and rule-driven, repetitious work activities started to play a major role. Whilst helping companies make greater profits, it also reduced the number of jobs as the demand for labour decreased and the demand for higher-level knowledge and skill sets increased. The workforce, entrenched in their low-level knowledge and skills sets, and lacking the more advanced level of knowledge and skills that arose out of automation, took industrial action as they fought to save their jobs and a period of disruption occurred: a period that saw the mass destruction of whole sectors of industry and the biggest change in the knowledge and skill requirements for productive work in 200 years.

The paradox of the Internet

But an even greater change was about to occur, one that few policymakers even remotely understood and so were fundamentally ill-equipped to deal with: the arrival of that most disruptive of technologies, the personal computer and all its derivatives such as the smart phone. Computerisation takes automation (and the associated field of robotics) to a whole new level of disruption. As any job that is rule-based, routine and repetitious can be done more efficiently and effectively by a computer – and most jobs are still rule-based, routine and repetitious – it is inevitable that computers will displace workers in a major way, something that started to happen in the 1990s as the ultimate disruptive technology, the Internet, became publicly and widely available.

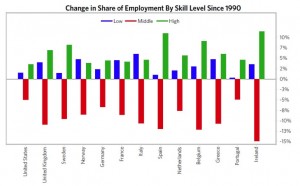

The pursuit of the advantages and benefits of the Internet and the hypertext protocols have led many organisations to create systems that are entirely driven by technology and operated by the end-users. Egov. is now the flavour of the times in most advanced economies and with its increasing sophistication, it is delivering huge parts of the governments’ operations in a highly efficient manner. This is just the most recent example of ‘consumerisation’ about which I have written three blog essays and although customerisation, once the customer has adapted their processes and procedures to its use, generally delivers major benefits to the customer and significant financial ROI and cost savings to the organisation, it has a massive ‘cost’ to society as is illustrated in this chart from Bridgewater Associates, quoted in the UK Business Insider.

According to the UK Business Insider, the chart is based on data from MIT economist David Author and shows that while the number of low-skilled jobs (labouring and craftwork) has grown and the number of high-skilled jobs (knowledge work) has grown significantly, the number of middle-skill jobs (generally those that require a full secondary education but little else) has fallen dramatically over the last 27 years.

According to the UK Business Insider, the chart is based on data from MIT economist David Author and shows that while the number of low-skilled jobs (labouring and craftwork) has grown and the number of high-skilled jobs (knowledge work) has grown significantly, the number of middle-skill jobs (generally those that require a full secondary education but little else) has fallen dramatically over the last 27 years.

In other words, the advent and adoption of Internet technologies and the development of heavily customerised user/supplier interfaces has resulted in a hollowing out of the types of jobs that are available in the advanced economies: low-skilled work is available, knowledge work is growing but the number of middle-range jobs is declining dramatically, which is going to put a lot of people out of work. The section of the workforce, those with no more than secondary education and possible years of experience, are suddenly going to find themselves part of the long-term, structurally unemployed. To get back into work, they will either have to downgrade to low-skilled jobs with the associated loss of status and reduced income, or else they will have to return to full-time education to up-skill themselves and obtain advanced knowledge and thus seek employment in the still small but growing knowledge work sector.

I recently came across an example of a governmental department that, at the beginning of the technology change, had 600 employees and now, a few years later, was a highly efficient organisation delivering an increased level of service with a reduced workforce of around 100 – and none of the 500 redundant workers had been able to find a job at a similar level and salary scale as before. Those 500 were now long-term and structurally unemployed, and costing the government in terms of social security.

Essentially, the chart above shows that all the developed economies of Europe, with the addition of the USA, face a long-term trend towards rising structural unemployment, rising demands on the social security/unemployment benefits system, decreased levels of disposable income, decreasing growth, possibly decreasing GDP, increasing levels of poverty and a widening poverty gap. To address this sort of issue will require changes in political policy, but there appears little recognition of the issue at the national political level and certainly no policies are being put forward. Instead, political leaders from the US President, Donald Trump, and the UK’s Brexit-preoccupied PM, Theresa May, to the Commissioners of the European Commission, are all blandly talking about job creation and economic growth. Somebody needs to take action soon!

Having looked at the irrationality of human economic behaviour, Alasdair White takes another look at consumerism and concludes that major changes in consumer behaviour have already occurred, and that consumerism as we have experienced it for the last 70 years is now effectively dead.

Human behaviour is a response to stimuli experienced. The actual behaviour demonstrated is the result of learned responses that are deemed rational or irrational, acceptable or unacceptable, within the norms of a society or other bounded environment within which the person exists, and we all respond differently to different stimuli depending on the experiences we have had in the past. As a result there is no robust evidence that human behaviour is predictable at the individual level, but there is evidence that socialisation, fashion and societal norms play a strong part in governing behaviours and channelling them into what can be considered acceptable or normal. Our economic behaviour is no different.

In the developed or ‘old’ economies around the world and especially in Europe and North America, the dominant economic behaviour of the last 70 years has been based on ‘consumerism’ and its closely related cousin, ‘materialism’. Consumerism is a model in which an ‘economic actor’, the individual consumer, purchases a good (or service) which he or she does not necessarily need, uses it, and then disposes of it before the end of its useful life, before buying a replacement. Materialism is a ‘greed’ model in which we ‘value’ ourselves and others based on the material possessions we or they possess. And there are those who would argue these are the directed result of ‘capitalism’.

Now, the fact that materialism and consumerism are most obvious in capitalistic environments, and generally do not arise to the same extent in non-capitalistic environments, does not make ‘capitalism’ a causation factor as both are behavioural responses to psychological stimuli that exist outside the narrow definitions of the models developed in an attempt to explain our economic behaviour.

Let’s unpack the concepts so that what is really happening becomes clearer. Consumerism has an economic actor – a human engaged in deciding to buy from a supply of goods or services which he/she may not ‘need’. Now, a ‘need’ is a good or service that is essential to the economic actor’s survival in the environment which he inhabits. At the basic and most fundamental level, a ‘need’ is a physical or emotional requirement without which the human will die: according to the 20th century American psychologist, Abraham Maslow, these include food and drink, protection from the elements and other dangers inherent in the environment, air to breath, warmth, sex and sleep. This is, perhaps, too restrictive a definition in today’s environment and has been too narrowly interpreted. It has been suggested that such things as smartphones can also be considered ‘needs’, given that in the modern developed world it is virtually impossible to survive effectively without them – this is a moot point.

The definition then goes on to talk about ‘using the good’, which is self explanatory, and ‘disposing of the good before the end of its useful life’. Perhaps one of the most vivid examples of this is the above-mentioned smartphone: I frequently ask my graduate students about their smartphone and all claim it is, for them in their western European world, an essential, but all admit to having acquired at least one replacement smartphone before their existing one had ceased to function – indeed, most of my students are on their sixth or seventh smartphone.

Clearly for consumerism to exist there needs to be a large range of goods or services available but there also needs to be a ready supply of money in the form of discretionary disposable income. Disposable income is that part of the economic actor’s income (or funds) that is in excess of that which is required to fulfil real survival needs such as housing costs, food and accommodation and the whole range of what we have come to regard as the regular fixed expenses of our lives. Disposable income is, however, often subject to periodic spending cycles for such things as social needs and so, in this case, the term ‘discretionary’ refers to that proportion of the disposable income that the economic actor can choose to spend on goods or services that are non-periodic.

So far so obvious, perhaps, but in economic terms, discretionary disposable income is a direct result of the development of a middle-class. Prior to that, those at the bottom end of the economic scale, the vast majority of economic actors, had just enough income to enable them to cover their survival costs, and often not enough even for that. While those at the top of the economic scale, those who owned the business and the land, had plenty of discretionary disposable income but made up only a small fraction of the economic activity. Once a critical mass of middle-class is achieved, we see the development of those wishing to supply it.

In the 1930s, consumerism was a far-off event: the emergent middle-class had taken a battering with the Great Depression, the impoverished majority had little disposable income, never mind discretionary disposable income, and there was no real range of goods.

The start of World War Two changed all that and created all the conditions for consumerism to arise, first in the USA, then in Europe.

In the USA and the UK, the demands of warfare created a massive boom in innovation, both in terms of technology but also in methods of production with the adoption of advanced versions of Ford’s production-line manufacturing. It also brought a mass intake of women into the labour force … and these women found themselves for the first time as breadwinners, family decision-makers, and financially independent. All this played to the strengths of the ‘anglo-saxon’ national cultures (see the work of Geert Hofstede) with their high levels of individualism, independence, competitiveness and success-driven self-confidence, and their relatively low levels of hierarchical power distribution.

By the end of 1946, experience of the war had wrought a profound change in the societies of the USA (in particular) but also in the UK … they had won the war based on their industrial might and national characteristics and they wanted to reap the benefits. The men had put their lives on the line for six long years and wanted well-paid jobs that delivered a high sense of self-worth and delivered the material benefits of a changed world. The women, financially independent and used to making decisions, had no desire to return to the domestic existence that had been their lot pre-war. But for the manufacturing companies facing the end of the demand-driven boom years of the war, the change was potentially catastrophic: they urgently needed two things, (1) new product lines and (2) a strongly growing domestic demand plus export markets.

Manufacturing enterprises were the first to react and in a burst of innovation they quickly adapted the new technologies and production methods to producing items that matched the peace-time demands for labour-saving devices and the need to be released for domestic ties. Washing machines and refrigerators replaced tanks and planes, the vacuum-cleaner was developed, affordable cars replaced military vehicles, radio and then television were developed, and the whole lot were supported by the hard-sell strategies of the new advertising agencies as they ‘created’ the demand. All this was focused ruthlessly on the new aspiring middle-class families of suburban and small-town America … and they responded, creating an advertising-led, supply-driven or ‘push’ demand.

But there was a finite size to the domestic market and the US government was not slow in the creation of the Marshall Plan in which American funds were distributed to re-build war-ravished overseas economies so they could absorb the growing supply of US-made consumer goods. As early as the 1930s, manufacturers realised that selling just one unit to a buyer was wasteful and so designed their goods to become obsolete, no-longer functional and/or unfashionable after a certain time frame. By the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, planned or built-in obsolescence was the norm, thus forcing buyers to continually upgrade or replace their appliances and goods. In 1960, Vance Packard, a cultural critic, published a book called The Waste Makers as an exposé of ‘the systematic attempt of business to make us wasteful, debt-ridden, permanently discontented individuals’ perpetually seeking the latest most fashionable version of products even though the current version still had life in it. Indeed, the post-war manufacturing boom created the consumer demand which led inexorably to the human economic actor becoming irrational to an extreme degree. Consumerism was a self-destructive and non-sustainable model but the consumers, faced with an ever growing and more sophisticated array of goods and unable to resist their debt-driven gorging, had accepted it as both desirable and inevitable.

The ability of advertisers to ‘create a demand’ for goods and the advances in miniaturisation and computing led to a second major wave of innovation in the 1990s, something that lasted until the early years of the 21st century. This second wave of innovation in manufactured goods started slowing before 2010 and is now finally well towards the bottom of the down-wave, and focus has shifted to making the current technologies do more with the development of software and ‘apps’.

Interestingly, politicians and economists have not fully understood the linkages inherent in the consumer model and it wasn’t until 2008, when the financial and banking sector imploded so spectacularly, that the debt-driven binge-buying that had created asset bubbles out of all proportion to their value finally registered with the consumer as being absolutely not in their self-interest, and they stopped spending, started saving, and reduced growth of western-style economies to almost zero. Inflation also shrank to almost 0%, something very much in the economic best interests of the consumer, but politicians beat their collective chests and appealed to the consumers to start spending again. Regulation was introduced to encourage individuals to return to being in debt, economists bleated about the need for inflation, politicians told their electorate they were being irresponsible by not spending or wasting their money … but the consumers have been resolute, mostly, and the great over-inflated consumer bubble has burst.

And with that burst bubble has come the inevitable result: manufacturing companies needed to downsize, stock piles grew and pushed prices down even further (very much in the rational self-interest of the human economic actor), manufacturers are more or less having to give away their goods just to generate cash-flow, technology and innovation has created new ways of doing business so there is a glut of commercial properties, both office and retail, people are using the technology to shop on-line and are better informed about the products thus making retail space much less important, which in itself results in the current glut of empty high-street shops, and even the huge generalist retailers are experiencing no or slowing growth, opening the way for artisanal and specialist retailers closely linked to their manufacturing base.

Having abandoned the self-destructive and irrational behaviour that drove the consumer model, the modern consumer is now more picky about what they buy and what service they expect, we have moved solidly away from a supply-side-driven push environment to a demand-side driven one that is opening the developed economies in a way that allows those manufacturers using just-in-time methodologies to dominate. The critical decision-making factors are now about life-style choices –consumerism is not dead nor will it die, but consumers are more critically aware, better informed, willing to spend but demanding better durability, better performance and better reliability for their money. Personal debt mountains are shrinking, inflation-driven asset markets such as housing are slowing, and the economic world has changed profoundly.

Alasdair White is a professional change management practitioner, business school professor, and behavioural psychologist with a keen interest in behavioural economics. He is the author of four best-selling business and management books and, under the pen name of Alex Hunter, has published two thrillers. April 2016

In this essay, Alasdair White takes a cold hard look at the current state of consumerism as an economic model and with the help of Daniel Kahneman and Nassim Nicholas Taleb concludes that consumerism and classical microeconomic theory is no long sustainable – it’s time for a re-think!

Are consumerism and the consumer society dead? Well, we’re all consumers but we don’t all live in a consumer society. This begs the questions as to what are consumers and what is a consumer society.

Consumers are those people who acquire, usually by buying, goods and services and then use them before disposing of them, often before the end of their useful life. This has given rise to the idea of a consumer society, which is one in which people often buy new goods, especially goods they want but do not need, and place a high value on owning many things. This, in many ways, is another way of describing economic materialism which is the excessive desire to acquire and consume material goods. It is usually closely connected to a value system that regards social status as being determined by affluence as well as the perception that happiness can be increased through buying, spending and accumulating material wealth.

In purely economic terms, this is directly contrary to the rational self-interest of the individual as an economic actor, a self-interest that is rationally served by the optimisation of the person’s scare economic resources – or, in other words, is best served by getting the best value for the limited money they have available. Very few people have an unlimited source of funds – almost all of us have income which is taxed leaving us with a disposable income from which we have to purchase the goods and services we ‘need’ (the goods and services that without which our health will decline and we will eventually die). This then leaves us with a discretionary disposable income with which to purchase those goods and services we want – and to do that we make decisions as to what to purchase so that we optimise our spending to acquire goods and services that have the greatest value to us. This element of choice, this discretion, means that we can choose to spend now or to save so that we can spend later (deferred expenditure). It also means we can choose to spend on goods that have no essential value but which satisfy an emotional need.

If we are rational, then we will seek to optimise our expenditure and only purchase those goods that are needed and present the greatest value to our long-term self-interest. This, of course, is the direct opposite of what the sellers of goods require us to do. The sellers (or retailers) are operating a business model that requires them to do everything they can to maximise the consumers spending – in other words, to get the consumer to spend the maximum possible amount irrespective of value or need. There is no possible situation in a consumer society in which a retailer can ever act in the consumers’ best interests as the economic objectives of the retailers and the consumers are mutually exclusive.

But why don’t consumers realise this? Why do they persist in believing that the offers from retailers represent something that will benefit them?

The answer is remarkably simple: people are not rational and seldom act in their own best interests. They are easily manipulated, usually by appeals to their emotions, and they seldom think things through to determine what course of action is actually in their real best interests. Essentially people are intellectually lazy, easily swayed by the opinions of others, and in many cases totally unable to think things through. This is where the work of Daniel Kahneman is of such importance. In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman explores the two types of thinking that appear to take place in the human brain. The dominant type is the Fast thinking (system 1) which creates heuristic models – experienced-based problem solving methods that use readily available information (and memories) that may be only loosely applicable and appropriate and usually render a sub-optimal (though often ‘good enough’) answer that contains systematic errors or cognitive biases. We tend to rely on these heuristics even when we shouldn’t, believing that our experience in similar such situations is appropriate in the current situation. This is simply not rational.

In comparison, the Slow thinking (system 2) engages in detailed analysis of all the information available to reach conclusions that a free of cognitive biases, systematic errors and requires consistent and conscious thought. It generally operates in a ‘bounded rationality’ but is still far more accurate than system 1, however it is an energy-intensive and costly process that takes significant amounts of time although it at least ensures that the subject is properly studied and a rational decision is made.

Why do we, as humans, allow our brains to adopt system 1 thinking at the expense of rationality? This is not explored by Kahnemen, possibly because the answer is not to be found within the field of psychology, but within biology. Studies show that an average human being has a resting metabolic rate of 1300 kcals per day (obviously this is dependent on age, gender, size and health, but this is an average) and the brain, which is about 2% of the body weight, consumes around 20% of that just to maintain its normal resting activity – about 260 kcals per day, but when the brain engages in system 2 thinking, the energy consumption increases dramatically and the amount of energy the body needs increases accordingly. This is empirically obvious to anyone who has been a student or has worked with students (or senior school pupils), at the end of a long day of study, they are exhausted and often fall asleep or need to consume high calorific foods before they can do their private study or homework – it is also measurable by studying blood glucose levels and other blood chemistry factors. Now, my hypothesis is that the brain has evolved in such a way that it has learned that deep thinking is costly in terms of energy and, as sources of energy are limited, it has set up decision-making and problem-solving methodologies (heuristic models) that make far lower energy demands while at the same time creating sub-optimal but ‘good enough’ solutions. In other words, our brains have evolved to use non-rational techniques as a way to save energy.

Obviously, if the system 1 heuristics are based on appropriate experiences, then they will become progressively more accurate in their outcomes and so less system 2 thinking has to be undertaken thus releasing the brain to engage in other activity without creating a spike in demand for energy. This, of course, is the basis of repetition or rote learning, repetitive practise, and our ability to provide ‘good enough’ solutions to most of our day-to-day activities. Kahneman builds on this by suggesting that when we do engage in energy-intensive system 2 thinking, the outcome can then be used from the memory and can inform the appropriate heuristic bringing its outcome closer to the optimal.

But Kahneman identifies something else that the brain does which makes our system 1 thinking sub-optimal and that is that the correct frames of reference for the problem, the understanding of risk and probability, and correction of our emotional biases are all active in system 2 but are not active in system 1. Such is our addiction to mistakenly believing that we are rational, we end up believing that all actions have an identifiable cause and if we can identify the cause, then we can control our response. But the shocking truth is that a great deal of what happens to us and in our environment is random in that there is nothing we can do to neutralise the cause or avoid the consequences. This school of thought is brought into clear focus by Nassim Nicholas Taleb whose work on randomness and risk is worth the effort (system 2) of reading and by ‘chaos theory’ which shows mathematically that very small differences in initial conditions (which may have existed at some indeterminate time and location in the past) can yield widely diverging outcomes in otherwise identical systems thus rendering long-term prediction of the outcome impossible. Both these concepts can and do invalidate the predictability which is a fundamental belief in micro-economics (and much else).

The truth of the matter is that behavioural psychology has undermined the foundations of micro-economic theory to such an extent that much of what we have been told is true about our economic activities is in fact unreliable. Take the prevalent and popular consumer model that is promoted so strongly by many societies, particularly western ones. This is, ostensibly, a market-economy model in which supply and demand play a dominant role so that rising demand for goods is matched by rising supply of those goods. But when we delve deeper, it becomes evident that the ‘market’ is a creation of the ‘supply-side’ elements – the producers and retailers – and not of the ‘demand side’ – the consumers. Let me explain.

During the world war that took place between 1939 and 1945, production was revolutionised, no longer were things made by artisans and by hand, machines were created and employed to mass produce the materials of war – everything from ammunition to aircraft were produced on a production line basis that churned out usable end products at a phenomenal rate. This was a classic ‘demand side’ situation: the military required huge quantities of everything and industry geared up to provide it. Costs were not a problem as governments simply printed money or the banks lent it and so production (a supply side element) knew no bounds. The problem was that after 1945/46 demand fell precipitously leaving the economy with a huge ‘over capacity’ on the supply side.

The solution, as far as the policy makers were concerned, was firstly to convert from the production of weapons to the production of consumer products (but involving the same technologies) and then to artificially create a demand via the promotion of consumption through advertising, marketing, bank loans, and governmental policy. Much of this was focused on creating a desire to own goods and services, irrespective of need, and the award of status for owning lots of material possessions. In other words, the creation of a consumer society to provide ‘demand’ for the over abundance of ‘supply’. Little attention was paid to whether these goods were needed, they were presented as being the rightful entitlement of the victors of the recent war: in other words, this was the reward for the privations and destruction endured. All the supply side actors were involved: banks lent money to consumers so that they could buy goods, producers made goods irrespective of need or value, advertisers and the media promoted the idea that greed was good and that owning lots of things was our entitlement and a desirable thing, that it gave us status.

Somewhat inevitably, there were just so many washing machines and other items that any one family could use and so producers started to build in obsolescence, they started creating products that were deliberately designed to break down after a certain period of time so that the consumer felt compelled to purchase a replacement – something that is certainly not in the best interests of the consumer and his or her need to optimise their economic activity, but certainly something that maximised the producers’ side of the equation. It didn’t take long for the consumer to become addicted to this bonanza of products and to create a huge demand bubble that was promoted by advertising and marketing communications in the media and fuelled by cheap loans from the banks.

Inevitably, these bubbles burst, lenders found themselves exposed to defaulting borrowers, many of whom should never have been allowed to borrow in the first place, greed had turned the lenders and the consumers into gluttons, more and more producers were entering the market thus inexorably inflating the supply side while squeezing the demand side by cutting off the supply of money that fuelled the consumer boom. Eventually, the consumers got the message that greed was NOT good, that the markets were a zero-sum game in which people could only obtain if someone else lost. It was not a win-win situation but a strictly win-lose with the consumer on the losing end. Eventually, the consumers stopped consuming, demand dried up and the supply side producers started to cry foul and pressurised their governments ‘to do something to stimulate demand’ – the governments, blinded to the reality of the simple win-lose equation and made up of normal non-rational thinkers, obliged and the result is the monumental mess the western economies are in as we enter 2014.

Bizarrely, governments are even telling us that we should not save our money (deferred spending) but we should spend now. These are the same governments that have no way of funding the pensions that will have to be paid and have been telling people to save for their own retirement. Well, rather obviously, we cannot spend now and save for our retirement … but there again, politicians are not known for their rationality.

Alasdair White is a business school professor, author and publisher. He is the author of three best selling management books and under his pen-name of Alex Hunter, the author of two thrillers.