Posts Tagged ‘behavioural economics’

Over the last twenty years, the global economic model has been under stress as more and more people around the world have come to recognise that the benefits of the economic model are very unevenly distributed. However, it is only in the last ten years since the collapse of the global banking sector that we have seen political shifts towards nationalism, isolationism, and extremism. Pundits, especially in the media, have fanned the nationalistic flames, and generally drawn the wrong conclusions as to the cause of the problem. In this essay, Alasdair White argues that all the ‘…isms’ are, in fact, the result of a desperate regression to the extremes of national culture.

Back in the early 1990s, empirical evidence came to light that, when faced with a severe shock or downturn, organisations with a strong organisational culture found it quickly abandoned, followed by a sharp regression to national cultures. The greater the shock, the greater the regression towards the extremes. At the time, there was little in the way of robust data or research on this phenomena, for example Hofstede’s ground-breaking work on national cultures, published in 1980, was only just coming into the wider non-academic word, and the GLOBE Project (House) had yet to be created. But even without such models it was obvious that such a regression had occurred as the result of a shock.

Such a shock occurred in 2007/2008 when the banking sector broke its operating model and basically crashed a major part of the world’s financial system. The result has been an extended period of economic hardship that has seen unemployment rise as a result of lack of finance and the deployment of technology, a radical shift in focus away from the cost-heavy manufacturing sector towards the service sector, and a decline in spending power as wages decline or stop, savings dry up or are rebuilt, and people stop spending. For many, this has been an opportunity to re-prioritise their financial objectives and make life-style decisions, but for others it has brought hardship.

Unsurprisingly, the threat to living standards, the threat to the economic operating model, and the general decline in discretionary disposable income across the entire developed world has bought people up short and a regression to the extremes of national cultures was, I suggest, almost inevitable. In the USA we have seen a regression to an extreme version of republicanism with its associated isolationism and protectionist policies. In the UK we have seen a rejection of collectivism, a breakdown in collaboration with its trading partners, and a sharp rise in extremist nationalistic tendencies: xenophobia and extreme anti-immigration is on the rise, authority of all types is being challenged, the ‘approval ratings’ of all shades of politician are at a very low level, and there has been an increase in the ‘me’ culture, a decline in the willingness to help others, and a rejection of supranational groupings. In Europe, after an initial rise in nationalistic politics, people have rejected the political elites and reverted to more localised groupings, and have reaffirmed their belief in strong supranational institutions such as the EU. People from the developing economies of Africa and the near East, fleeing the depressed economic opportunities in their own countries, have headed for the EU in worrying numbers.

All these trends and events are, I suggest, symptomatic of cultural shock and represent a significant reversion to the more extreme ends of national cultures. Let me explore this idea by using Hofstede’s 6-D Cultural Model to examine the UK’s decision to leave the EU.

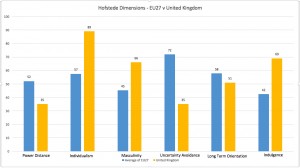

A discussion of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions can be found at https://www.geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html. In the graphic above, the UK (the right-hand column in each dimension) is compared to the average score of the rest of the EU-27 excluding Cyprus for which there is no meaningful data. As can be seen, the EU-27 average suggests that a significant difference exists between the UK and the rest of the EU in five out of the six dimensions.

When viewed through the prism of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions, the United Kingdom is a society with a low tolerance of hierarchical power and a strong tendency to question authority structures resulting in a society which, as Hofstede puts it ‘…believes that inequalities amongst people should be minimized’. At the same time, the UK is highly individualistic in that its people are expected to find happiness through individual fulfilment, which has given rise to a rampant self-centred consumer culture that appears to be based on greed (conspicuous consumption). According to Hofstede, the culture is success-orientated and driven by competition and achievement, with success being defined as being the winner or best in field. The low uncertainty avoidance score indicates that the UK is happy with ambiguity and is willing to ‘make it up as they go along’; this is reflected in their lack of detail-orientation in which the end objective is clear enough but the ‘how’ only emerges within a changing environment. Finally, the UK generally possesses a positive attitude and a tendency towards optimism.

On the other hand, the rest of the EU is comfortable with hierarchies and power structures, and does not particularly feel that inequalities between peoples should be minimized. However, they have a significant tendency towards a collectivist approach in which people, as Hofstede puts it, belong in groups that will take care of them in exchange for loyalty, a fact borne out by the low masculinity score that indicates that quality of life and blending in are a sign of success. This can be expressed as ‘liking what you do’ as being more important than wanting to be the best. When it comes to uncertainty avoidance, it is clear that the rest of the EU feels threatened by ambiguity and the anxiety it brings, and has constructed concepts and institutions, such as the EU itself, to try to minimize these. As a result, these societies accept the need for restraint in terms of their individual desires and impulses.

This comparison suggests that the way the cultures of the UK and those in the EU-27 have developed and evolved have resulted in there being strong and definite cultural differences between them. Indeed, the question that comes to mind is how and why did the UK and the EU ever think they could get along – perhaps Brexit is an inevitable divorce driven by the clearly quite different objectives and cultural qualities of the two parties. The ‘shocks’ emanating from the financial sector collapse in 2007-2009 have, I contend, acted as a catalyst, and caused the UK and the EU to regress to their more extreme cultural positions.

This significant set of differences between the UK and the EU-27 will now play out in the Brexit negotiations. The UK will focus on ‘winning’ the negotiations and getting ‘what’s best for Britain’ without a care for what is in the best interests of both parties. This win-lose strategy is going to be confrontational and is likely to result in a deal that neither side wants, one in which the UK is more likely to be the long-term loser and will find itself marginalised. The UK media will, undoubtedly, present this as the EU seeking to humiliate and punish the UK and, as they have done for as long as the UK has been in the EU, they will go on about the unelected bureaucrats acting in an undemocratic manner towards a democratically mandated government, thus primarily demonstrating their own lamentable ignorance about how the EU works. Undoubtedly this will play well in the eyes of those seeking a UK exit from the EU, but it merely demonstrates how under-informed both the media and the ‘leavers’ really are about what is happening.

The EU-27 position will be that the UK will need to step back from confrontation and to negotiate in a collaborative way, respecting the opinion of others and recognising that the EU-27 is by far a bigger enterprise than the UK and will act in its collective best interests. The UK will have to meet its collective obligations and recognise that it will not be able to ride rough-shod over others to obtain its own way. While the UK will be negotiating with a win-lose strategy, the EU will be seeking a win-win, and the outcome may well be a lose-lose.

Does it have to be this way? Of course not, but the individualistic, competitive and greed-driven UK politicians are unlikely to allow cooler heads to prevail. The loose cannons amongst the ministerial Brexiteers: David Davis, Boris Johnson, Liam Fox, egged on by the right-wing UKIP demagogue, Nigel Farage, will need to be reeled in and silenced while the ‘hard Brexit’ PM, Theresa May, will need to step back and allow the professionals to deploy a well thought through strategy that has a detailed plan backing it. Instead, what is more likely to happen is that the politicians will make up policy on the hoof in the name of retaining flexibility. All this will be anathema to the EU-27 negotiators who will have serious trouble accepting the resulting ambiguity and the UK’s constantly changing objectives and policies: they will want clarity and certainty and a linear, step-by-step approach.

Already, the Brexiteers are putting out smoke, claiming that at the end of the two-year period the UK may just have to walk away without a deal. This is, of course, not a practical solution for the UK as they will then have the worst of everything: no trade deal with their biggest trading partner, no trade deals with the rest of the world, and a reputation for not abiding by the terms of the treaties and contracts they have entered into, thus labelling themselves unreliable trading partners with little or no respect for the law. The EU-27 will, on the other hand, be left with a political and organisational mess, and the increased likelihood that other disgruntled countries will also seek to go it alone. Voilà, everyone’s a loser.

This divorce maybe inevitable but it doesn’t have to be divisive. So instead of regressing to the extremes of national culture, everyone needs to start thinking more clearly about their own enlightened self-interest in what is an interconnected global environment – one that is distinctly more collaborative (in national cultural terms) than the individualistic and self-centred British seem to believe.

Alasdair White is a lecturer in Behavioural Economics at UIBS, a private business school with campuses in Brussels and Antwerp, as well as Spain, Switzerland and Japan. He is the internationally respected and much cited author of a number of business and management books and papers, and a historian and authority on the Napoleonic era.

Politicians, especially those in the USA and the UK, talk boldly about the creation of new jobs, growth and the increase of wealth as a result of their policies, and something similar is being heard right across the EU from Commissioners and MEPs through to national politicians. Their self-belief is ‘wonderful to behold’ but is it built on any firm foundation? There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that they have, essentially and dangerously, assumed that the future can be built using the out-dated policies and ideas of the past. Behavioural economist and business school professor, Alasdair White, argues that the future is based on the current trends and rather than simply assuming that current policies and theories will deliver the hoped for future, it is time for a serious re-think, it is time to look at the reality of the trends, and to conduct a thorough going review of policy. It is time for some serious soul-searching.

A brief history of work

Back in the 1980s, Peter Drucker, the management theorist, suggested that most work could be characterised as being one (or a mixture) of four types: labouring (making or moving things), craftwork (using special tools to make or move things), technical (using technology such as machines to achieve an orders-of-magnitude advance in the efficiency of making or moving things), and knowledge work (the creation of knowledge or the pure application of knowledge). Such a linear analysis may be too simplistic but it hints at what may now have become a significant issue: that the nature of the work being done, and thus the skills and knowledge to do it, may have changed in such a way that has not been fully recognised.

If we go back just over 300 years to the late 1600s, the majority of the workforce was engaged in agriculture, the work of which ranged from simple labouring to craftwork. The knowledge and skill sets required for the agricultural labourer were minimal, generally not requiring any formal education, with experience of the repetitious nature of the work filling any knowledge deficiency. For the craftwork of the period, such as blacksmithing, an apprenticeship to an existing craftsman served to provide the worker with the requisite practical knowledge and skills, but usually not the theoretical knowledge. This situation did not change much for the next 100 years, even though there were technical advances in the form of seed drills and other machinery that delivered orders-of-magnitude improvements in efficiency thus increasing agricultural revenue, both as a result of increasing yields and of reducing the number of labourers required to work the land as many were heading to the growing cities and the industrialised workforce.

In the early 1800s, Europe was subjected to continent-wide war that then spread to all parts of the globe as France with a varying collection of allies competed with Great Britain and its allies to control world trade. The outcome was the growth in demand for war materials such as weapons, ammunition and ships, with an accelerating shift in the labour force from agriculture to early-industrialised production of non-agricultural materials. Although this created the foundation of the industrial revolution and the urbanisation of the population, it didn’t change the nature of the work: it was still labouring, utilising a minimal knowledge and skill set.

This trend continued right the way through to 1940 when World War II massively increased the demand for production of war materials, to an extent that created an imbalance between supply and demand of labour and production capacity. The problem was resolved by the development of production techniques through the introduction of mechanisation but there was still little need for a more skilled or a more knowledgeable workforce. Even the shift in the 1950s to a consumerist economic model and the diversification away from large-scale goods towards small consumer goods did little to change the nature of the work being done: the majority was still labouring and doing craftwork, although increasing mechanisation was moving some sectors into a technical work categorisation.

Fitting the workforce for the work

Throughout all this, the education systems were meeting the demand for minimal knowledge and skills. The gentle upward trend for increased knowledge had seen the establishment in 1870 of compulsory education in the UK up to the age of 10; this increased to 11 in 1893 and to 13 in 1899. In 1914 the school leaving age in the UK rose to 14 and then in 1944 it was set at 15. It stayed at 15 for the next 28 years before rising to 16 in 1972 and has stayed there until today, although now a child in the UK has to either stay in full-time education until they are 18 or to take part in an apprenticeship or other authorised training that must last until they are at least 18 years old. Whichever way this is examined, it is clear that, at least in terms of public policy, a child is considered to have obtained all the knowledge it needs to be a useful member of the workforce and of society by the time it is 16 (or possibly 18).

But the correlation between the knowledge and skill sets required in the world of work and that provided by the education system has now been broken – and has been out of step for the last 30 years or more. However governments have yet to address this. Let me explain.

In the late 1970s and into the 1980s, as companies driven by the demands of shareholder value and shareholder ROI sought greater efficiency in their production systems, automation of routine and rule-driven, repetitious work activities started to play a major role. Whilst helping companies make greater profits, it also reduced the number of jobs as the demand for labour decreased and the demand for higher-level knowledge and skill sets increased. The workforce, entrenched in their low-level knowledge and skills sets, and lacking the more advanced level of knowledge and skills that arose out of automation, took industrial action as they fought to save their jobs and a period of disruption occurred: a period that saw the mass destruction of whole sectors of industry and the biggest change in the knowledge and skill requirements for productive work in 200 years.

The paradox of the Internet

But an even greater change was about to occur, one that few policymakers even remotely understood and so were fundamentally ill-equipped to deal with: the arrival of that most disruptive of technologies, the personal computer and all its derivatives such as the smart phone. Computerisation takes automation (and the associated field of robotics) to a whole new level of disruption. As any job that is rule-based, routine and repetitious can be done more efficiently and effectively by a computer – and most jobs are still rule-based, routine and repetitious – it is inevitable that computers will displace workers in a major way, something that started to happen in the 1990s as the ultimate disruptive technology, the Internet, became publicly and widely available.

The pursuit of the advantages and benefits of the Internet and the hypertext protocols have led many organisations to create systems that are entirely driven by technology and operated by the end-users. Egov. is now the flavour of the times in most advanced economies and with its increasing sophistication, it is delivering huge parts of the governments’ operations in a highly efficient manner. This is just the most recent example of ‘consumerisation’ about which I have written three blog essays and although customerisation, once the customer has adapted their processes and procedures to its use, generally delivers major benefits to the customer and significant financial ROI and cost savings to the organisation, it has a massive ‘cost’ to society as is illustrated in this chart from Bridgewater Associates, quoted in the UK Business Insider.

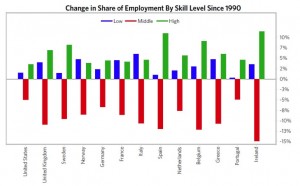

According to the UK Business Insider, the chart is based on data from MIT economist David Author and shows that while the number of low-skilled jobs (labouring and craftwork) has grown and the number of high-skilled jobs (knowledge work) has grown significantly, the number of middle-skill jobs (generally those that require a full secondary education but little else) has fallen dramatically over the last 27 years.

According to the UK Business Insider, the chart is based on data from MIT economist David Author and shows that while the number of low-skilled jobs (labouring and craftwork) has grown and the number of high-skilled jobs (knowledge work) has grown significantly, the number of middle-skill jobs (generally those that require a full secondary education but little else) has fallen dramatically over the last 27 years.

In other words, the advent and adoption of Internet technologies and the development of heavily customerised user/supplier interfaces has resulted in a hollowing out of the types of jobs that are available in the advanced economies: low-skilled work is available, knowledge work is growing but the number of middle-range jobs is declining dramatically, which is going to put a lot of people out of work. The section of the workforce, those with no more than secondary education and possible years of experience, are suddenly going to find themselves part of the long-term, structurally unemployed. To get back into work, they will either have to downgrade to low-skilled jobs with the associated loss of status and reduced income, or else they will have to return to full-time education to up-skill themselves and obtain advanced knowledge and thus seek employment in the still small but growing knowledge work sector.

I recently came across an example of a governmental department that, at the beginning of the technology change, had 600 employees and now, a few years later, was a highly efficient organisation delivering an increased level of service with a reduced workforce of around 100 – and none of the 500 redundant workers had been able to find a job at a similar level and salary scale as before. Those 500 were now long-term and structurally unemployed, and costing the government in terms of social security.

Essentially, the chart above shows that all the developed economies of Europe, with the addition of the USA, face a long-term trend towards rising structural unemployment, rising demands on the social security/unemployment benefits system, decreased levels of disposable income, decreasing growth, possibly decreasing GDP, increasing levels of poverty and a widening poverty gap. To address this sort of issue will require changes in political policy, but there appears little recognition of the issue at the national political level and certainly no policies are being put forward. Instead, political leaders from the US President, Donald Trump, and the UK’s Brexit-preoccupied PM, Theresa May, to the Commissioners of the European Commission, are all blandly talking about job creation and economic growth. Somebody needs to take action soon!

No one can have failed to notice the brouhaha over the UK’s EU exit referendum and it has been difficult to develop any real understanding, but in this blog, Prof. Alasdair White of the United International Business Schools in Belgium offers some ‘facts’ and voices his opinion.

The basic situation

The United Kingdom held a referendum which asked whether people thought Britain should be in or out of the EU. This referendum was advisory and legally non-binding and does not have to be acted upon. However, it will be politically difficult to ignore it.

The referendum does not trigger the ‘we’re leaving’ clause (Art.50) which can only be done through the correct constitutional process of the United Kingdom. There is absolutely nothing that the EU can do to ‘force’ the UK to send an Art.50 letter and the UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, has announced that, as he has resigned, he cannot do anything about Art.50, which now falls to his successor to deal with. Under the Conservative Party constitution, there is a due process that has to be gone through before a new leader can be announced and can take office, and the earliest this can happen is mid-September. Thereafter, the new Prime Minister has to activate the due parliamentary process to obtain legal authority to submit the Art.50 letter.

The due process is that a Bill has to be introduced into the UK Parliament calling for the repeal of the European Communities Act of 1972. This then has to be passed by both Houses of Parliament, and until that happens, the new PM has no authority to instigate the Art.50 communication. It is highly likely, in the circumstances, that the earliest that the Art.50 ‘we’re leaving the EU’ letter can be sent is late September and more probably towards the end of this year.

Once the letter has been sent, the process of ‘divorce’ will start and that will take many years. Art.50 foresees a maximum of two years but also foresees that, with the agreement of the remaining Member States, this could take much longer. When the final agreement is reached, then, and only then, will the UK leave the EU. Until that happens, the earliest being in late 2018, the UK remains a full member of the EU with all the rights, privileges and obligations that entails, just as it was before the referendum.

No need to panic

This means there is no need to panic! Once the temporary shock of the announcement has calmed down and Brexit has been factored into the ‘markets’, things will continue much as before. However, in the short term it’s going to be an uncomfortable and possibly turbulent ride.

For entrepreneurs in the UK, Brexit presents risks and opportunities. If their business is focused on the home market (i.e. the current UK) then it is very probable that they will suffer little major impact. On the other hand, if they are focused on exports (or are major importers), then their access to the world markets will be determined by what ‘deal’ has been struck in the leaving negotiations and what trade deals the UK has managed to put in place. The most likely scenario is that imports will cost more (and in some cases, a lot more) and exports will face tariffs that will make the goods more expensive in the markets.

A further complexity for UK entrepreneurs is that any EU funds from which they benefit in terms of market access, research, development, growth funds, etc., will cease and may well not be replaced by corresponding UK funds – the ability of the UK to replace those funds will be influenced by the state of the UK economy, which the ‘experts’ predict will be weaker, smaller, with higher taxes and lower government spending.

For entrepreneurs in Europe, their focus should be on where their market is. If they are exporters to the UK, or importers from the UK, then the new tariff regime resulting from what ever ‘deal’ is negotiated will have an influence.

All in all, European entrepreneurs will face significantly less risk as a result of Brexit than will those in the UK. They will also face significantly less risk to their funding and borrowing structures. And, frankly, there is time to plan how to handle the risks both in the EU and in the UK, but this needs to be thought about as soon as the UK sends in its Art.50 ‘we’re leaving the EU’ letter.

As far as opportunities are concerned, well, any major change provides opportunities provided there is flexibility of response. Business as normal will not be an option if Brexit becomes a reality but there is time to develop new products and new markets, as well as putting different funding structures in place providing action is taken as soon as Art.50 is triggered.

So, for entrepreneurs in both the UK and the EU there is no need for panic about Brexit, but there is a need to do a risk analysis and to plan a response to those risks. There is also a need to develop a new approach to the changed market conditions. However, there is time for some serious but unhurried thinking providing that thinking starts soon.

We live in ‘interesting times’, but for the enterprising business person there are opportunities to be taken as well as risks to be minimised.