Organisational Behaviour & Development

Critical thinking combined with evidence-based research is a powerful methodology for understanding and providing solutions in circumstances in which statistical research methodologies are either inappropriate or unsustainable. But if the facts are not recognised and accepted as facts and the problem is not recognised, understood or acknowledged, then no amount of critical thinking and evidence-based research will produce sustainable and valid solutions. This failure of reason is a now a very real issue in the modern world.

In this social media-driven world, most people don’t bother thinking, they simply rely on their intuition and heuristic responses as this is less like hard work: after all, they don’t have time to think and every moment is focused on reacting. Even amongst those who should be thinking, there appears to be a significant number for whom the classical empirical research methodology of developing a hypothesis after analysis of pre-existing theories, designing a data collection process, collecting data, analysing them using a statistically robust method, comparing and contrasting them with the results contained in the published literature before drawing conclusions is the only acceptable research model. This might be an acceptable approach with undergraduate and maybe graduate research but is hardly appropriate when considering post-graduate research, as such thinking rejects or choses to ignore what Albert Einstein called Gedankenexperiments (‘thought experiments’) or the use of critical thinking based on first principles and multiple sources of evidence to infer or deduce new knowledge and understanding.

Michael Scriven and Richard Paul suggested in 1987[1] that critical thinking…

| … is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness. | |

| It entails the examination of those structures or elements of thought implicit in all reasoning: purpose, problem, or question-at-issue; assumptions; concepts; empirical grounding; reasoning leading to conclusions; implications and consequences; objections from alternative viewpoints; and frame of reference. Critical thinking — in being responsive to variable subject matter, issues, and purposes — is incorporated in a family of interwoven modes of thinking, among them: scientific thinking, mathematical thinking, historical thinking, anthropological thinking, economic thinking, moral thinking, and philosophical thinking. | |

Whilst Karen Robinson (2009)[2] considered evidence-based research as being ‘the use of prior research in a systematic and transparent way to inform a new study so that it is answering questions that matter in a valid, efficient and accessible manner’.

But it is the lack of critical thinking and evidence-based research and the over-reliance on empiricism that has, on numerous occasions, led to a failure of reasoning, resulting in some avoidable catastrophe occurring.

In his 2005 book, Collapse, How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive, Jared Diamond, an American polymathic geographer and anthropologist, describes a range of cultures and societies from modern USA, back through medieval and iron-age Viking Greenland, to the ancient statute-carving Polynesians of Easter Island, and examines the critical steps each takes that led to the collapse of their societies.

Diamond’s thinking leads him to postulate a four-step failure model in which he describes what happens when societies fail to recognise, refuse to consider, or simply cannot address the issues that face them, and which then fundamentally undermine the critical assumptions that are the foundations of the societal models in operation. These factors lead to failures in group decision-making, resulting in catastrophic failures, including failures to survive:

- The failure to anticipate a problem before it arrives. This is similar to, and maybe a synonym for, the failure to understand that current short-term decisions may lead to future problems in what can be considered as the law of unintended consequences.

- The failure to recognise as a problem a problem that has already arrived. This can also be a refusal to recognise a problem as a problem because, in the short term, it doesn’t appear to be a problem. This is often associated with the failure to learn from history.

- The failure to attempt to solve a problem once it has arrived and been recognised. This is denial of, and a tendency to ‘turn a blind eye’ to, the issues. This often stems from the belief that things will resolve themselves or that someone else is responsible for solving the problem – a case of ‘passing the buck’.

- The failure to solve a recognised problem due to the problem and /or the solution being beyond the capacity and competence of the group to solve or is not in their short-term self-interest to solve. This may include being beyond the available resources of the group or because the group has lost the skills to resolve or address the issue. It also occurs when the group has a short-term socio-economic need not to solve the problem: in other words, they would lose political or economic power by doing so.

This four-step approach, which I will call the Diamond Collapse Hypothesis, does not, however, only apply to the anthropological study of societal collapse, it also has an application in the study of the historical decline of empires, the collapse of companies, the defeat of armies and, on a micro scale, it is central to the success or failure of critical thinking. And it almost always starts with the ability or inability of people to process and understand reality, and to define and then take action that will lead to rational and desirable solutions.

Although the underpinning concept is originally attributed to René Descartes (1596-1650), the Santiago Theory of Cognition (1972) proposes that ‘we do not perceive the world we see, we see the world we perceive’: in other words we each of us have our own ‘reality’ and this is entirely autopoietic , i.e. it is created by ourselves as a result of our cumulative personal experience. The result of this is that we believe what our experience has taught us to believe, even when the evidence suggests this is wrong. This blind adherence to a fixed set of beliefs seems to be the very antithesis of critical thinking and evidence-based research, and may well lead us to reject ideas that are not aligned with our own autopoietic reality. This was dramatically illustrated by Hans Rosling (1946-2017), a Swedish physician and statistician, in a TED talk entitled How not to be ignorant about the world[3] in which he showed that people have a highly distorted understanding of reality, one that is not even randomly wrong.

According to Rosling, this inability to grasp reality is caused by personal bias, reinforced by outdated knowledge taught in schools and universities, and coupled with biased news reporting. And it is then further embedded in our brains by what Daniel Kahneman (b. 1934) called ‘loss aversion’ in which we value what we have twice as much as what me might gain from changing our minds: thus we are very reluctant to abandon our current reality even when it is made absolutely clear that it is wrong and we would be significantly better off with a new reality.

It is this that underpins the first two parts of the Diamond Collapse Hypothesis: the failure to anticipate a problem before it arrives and the failure to recognise as a problem a problem that has already arrived. Putting it simply, our personal reality makes it difficult for us to believe that our actions and ideas may logically (and thus more or less inevitably) lead to failure. And, of course, once that failure (the problem) has arrived we often have too much political, social or economic interest invested in our personal reality that we deny the problem exists. This is what economists would call the ‘sunk cost fallacy’ in which it is better to continue to invest in a failure than to abandon it, cut our losses, and re-think the situation.

This process has been clearly visible in the recent past with the 2007/2008 sub-prime loans crisis in the USA’s banking sector in which it was obvious what the logical outcome would be, but too many bankers had too much invested in a disastrous scenario to be able to abandon it[4]. It is also evident in the 2016-2017 Brexit situation, in which too many politicians and other Brexit supporters had too much at stake in pursuing Brexit to be able to step back, abandon the process, and re-think their relationship with Europe[5]. It reminds me of what one wise business leader said: ‘the golden rule of holes is to stop digging when you’re in one’.

The third and last part of the Diamond Collapse Hypothesis, the failure to attempt to solve a problem once it has arrived and been recognised, is founded on a well recognised but often misunderstood behavioural response to stress: that of denial. This comes from the work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1926-2004), an American-Swiss psychiatrist whose pioneering work on terminally ill patients showed that when faced with a very unpalatable and deeply stressful future event, the mind created a behavioural response, which was to deny that the event applied to them. This denial was considered to be the first phase of a coping cycle that then led through anger, bargaining, depression, and finally to acceptance. This was subsequently built on by Colin Carnall (b. 1947), a management school professor, to illustrate people’s reaction to change[6] and I used it in my 2009 paper, From Comfort Zone to Performance Management. As denial turns to anger and then bargaining, this turning of a ‘blind eye’ to the problem appears to lead to two scenarios: the problem becomes undiscussable as it is ‘someone else’s problem to deal with’, or else it is thought to be unnecessary to deal with as it will simply go away if ignored.

This denial phase is evident in the USA in 2017 and 2018 in response to gun violence – it is undiscussable but it remains as a problem. It was also evident amongst British politicians in early 2018 during the Brexit ‘divorce’ negotiations between the UK and the EU when the subject of a ‘hard border’ in Ireland was raised. This was always going to be a problem if the UK were to leave the EU customs union and there are many who pointed this out even before the 2016 referendum to leave the EU: the problem was not recognised as a logical outcome of a course of action (Diamond Collapse Hypothesis stage 1), it was not recognised as a problem by the UK even when it was raised by the EU in early 2017 (Diamond Collapse Hypothesis stage 2), and by March 2018, the UK had still made no effort to come up with a workable and practical solution and continued to deny that it was a problem (there is even evidence in news reports of the time that the UK thinks it is someone else’s problem or that it can be negotiated away as part of a future trade agreement).

The fourth stage of the Diamond Collapse Hypothesis, the failure to solve a recognised problem due to the problem and/or the solution being either beyond the capacity and competence of the group to solve or is not in their short-term self-interest to solve, is the recognition that with the passing of time, the necessary knowledge, skills, attributes, competencies and capacity to solve the problem may have been lost: in other words, those tasked with solving the problem may simply not be able to solve the problem or it becomes simply too expensive to solve. At this stage the problem simply becomes overwhelming, the situation then collapses into total failure and has to be abandoned as unsustainable.

This may be the outcome for the Brexit negotiations since the UK believes that free trade agreements can be negotiated in two to three years despite all the historical data showing that, even when there are no impediments, trade deals take seven to ten years to complete. Thus the UK may cease being a member of the EU and, at the same time, have no trade deals in place with the inevitable consequence of a shrinking GDP and economy for a decade or so. This would be made worse by the fact that as of the beginning of 2018, the UK has no trade negotiation capacity or competency, as these have been lost due to not being involved in trade negotiations for many years whilst a member of the EU.

The inevitability of the progression of the Diamond Collapse Hypothesis can, of course, be avoided provided people engage in critical thinking and evidence-based research … but one has to admit that, as Kahneman talks about in his 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow, thinking is hard, and it is even harder for those not used to it, and it is far, far easier to react using our own preconceived ideas and autopoietic reality, even when they have nothing to do with the facts.

Alasdair White is a lecturer in Behavioural Economics at UIBS, a private business school with campuses in Brussels and Antwerp, as well as in Spain, Switzerland and Japan. He is the internationally respected and much cited author of a number of business and management books and papers, as well as a historian and authority on the Napoleonic era.

[1] http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766, accessed 21 March 2018.

[2] Robinson, Karen A. Use of prior research in the justification and interpretation of clinical trials. The Johns Hopkins University, ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing, 2009.

[3] https://www.gapminder.org/videos/how-not-to-be-ignorant-about-the-world/

[4] You would have thought a banker could spot a sunk cost fallacy a mile off, but no; they blindly carried on pouring money into these loans and eventually the whole bubble burst.

[5] The UK politicians, in particular, apparently felt that had they stepped back and said ‘this is wrong’ they would be unelectable for a generation.

[6] Managing Change in Organizations, Prentice Hall, 1990.

v.March2018

Politicians, especially those in the USA and the UK, talk boldly about the creation of new jobs, growth and the increase of wealth as a result of their policies, and something similar is being heard right across the EU from Commissioners and MEPs through to national politicians. Their self-belief is ‘wonderful to behold’ but is it built on any firm foundation? There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that they have, essentially and dangerously, assumed that the future can be built using the out-dated policies and ideas of the past. Behavioural economist and business school professor, Alasdair White, argues that the future is based on the current trends and rather than simply assuming that current policies and theories will deliver the hoped for future, it is time for a serious re-think, it is time to look at the reality of the trends, and to conduct a thorough going review of policy. It is time for some serious soul-searching.

A brief history of work

Back in the 1980s, Peter Drucker, the management theorist, suggested that most work could be characterised as being one (or a mixture) of four types: labouring (making or moving things), craftwork (using special tools to make or move things), technical (using technology such as machines to achieve an orders-of-magnitude advance in the efficiency of making or moving things), and knowledge work (the creation of knowledge or the pure application of knowledge). Such a linear analysis may be too simplistic but it hints at what may now have become a significant issue: that the nature of the work being done, and thus the skills and knowledge to do it, may have changed in such a way that has not been fully recognised.

If we go back just over 300 years to the late 1600s, the majority of the workforce was engaged in agriculture, the work of which ranged from simple labouring to craftwork. The knowledge and skill sets required for the agricultural labourer were minimal, generally not requiring any formal education, with experience of the repetitious nature of the work filling any knowledge deficiency. For the craftwork of the period, such as blacksmithing, an apprenticeship to an existing craftsman served to provide the worker with the requisite practical knowledge and skills, but usually not the theoretical knowledge. This situation did not change much for the next 100 years, even though there were technical advances in the form of seed drills and other machinery that delivered orders-of-magnitude improvements in efficiency thus increasing agricultural revenue, both as a result of increasing yields and of reducing the number of labourers required to work the land as many were heading to the growing cities and the industrialised workforce.

In the early 1800s, Europe was subjected to continent-wide war that then spread to all parts of the globe as France with a varying collection of allies competed with Great Britain and its allies to control world trade. The outcome was the growth in demand for war materials such as weapons, ammunition and ships, with an accelerating shift in the labour force from agriculture to early-industrialised production of non-agricultural materials. Although this created the foundation of the industrial revolution and the urbanisation of the population, it didn’t change the nature of the work: it was still labouring, utilising a minimal knowledge and skill set.

This trend continued right the way through to 1940 when World War II massively increased the demand for production of war materials, to an extent that created an imbalance between supply and demand of labour and production capacity. The problem was resolved by the development of production techniques through the introduction of mechanisation but there was still little need for a more skilled or a more knowledgeable workforce. Even the shift in the 1950s to a consumerist economic model and the diversification away from large-scale goods towards small consumer goods did little to change the nature of the work being done: the majority was still labouring and doing craftwork, although increasing mechanisation was moving some sectors into a technical work categorisation.

Fitting the workforce for the work

Throughout all this, the education systems were meeting the demand for minimal knowledge and skills. The gentle upward trend for increased knowledge had seen the establishment in 1870 of compulsory education in the UK up to the age of 10; this increased to 11 in 1893 and to 13 in 1899. In 1914 the school leaving age in the UK rose to 14 and then in 1944 it was set at 15. It stayed at 15 for the next 28 years before rising to 16 in 1972 and has stayed there until today, although now a child in the UK has to either stay in full-time education until they are 18 or to take part in an apprenticeship or other authorised training that must last until they are at least 18 years old. Whichever way this is examined, it is clear that, at least in terms of public policy, a child is considered to have obtained all the knowledge it needs to be a useful member of the workforce and of society by the time it is 16 (or possibly 18).

But the correlation between the knowledge and skill sets required in the world of work and that provided by the education system has now been broken – and has been out of step for the last 30 years or more. However governments have yet to address this. Let me explain.

In the late 1970s and into the 1980s, as companies driven by the demands of shareholder value and shareholder ROI sought greater efficiency in their production systems, automation of routine and rule-driven, repetitious work activities started to play a major role. Whilst helping companies make greater profits, it also reduced the number of jobs as the demand for labour decreased and the demand for higher-level knowledge and skill sets increased. The workforce, entrenched in their low-level knowledge and skills sets, and lacking the more advanced level of knowledge and skills that arose out of automation, took industrial action as they fought to save their jobs and a period of disruption occurred: a period that saw the mass destruction of whole sectors of industry and the biggest change in the knowledge and skill requirements for productive work in 200 years.

The paradox of the Internet

But an even greater change was about to occur, one that few policymakers even remotely understood and so were fundamentally ill-equipped to deal with: the arrival of that most disruptive of technologies, the personal computer and all its derivatives such as the smart phone. Computerisation takes automation (and the associated field of robotics) to a whole new level of disruption. As any job that is rule-based, routine and repetitious can be done more efficiently and effectively by a computer – and most jobs are still rule-based, routine and repetitious – it is inevitable that computers will displace workers in a major way, something that started to happen in the 1990s as the ultimate disruptive technology, the Internet, became publicly and widely available.

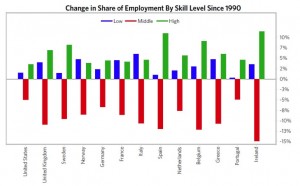

The pursuit of the advantages and benefits of the Internet and the hypertext protocols have led many organisations to create systems that are entirely driven by technology and operated by the end-users. Egov. is now the flavour of the times in most advanced economies and with its increasing sophistication, it is delivering huge parts of the governments’ operations in a highly efficient manner. This is just the most recent example of ‘consumerisation’ about which I have written three blog essays and although customerisation, once the customer has adapted their processes and procedures to its use, generally delivers major benefits to the customer and significant financial ROI and cost savings to the organisation, it has a massive ‘cost’ to society as is illustrated in this chart from Bridgewater Associates, quoted in the UK Business Insider.

According to the UK Business Insider, the chart is based on data from MIT economist David Author and shows that while the number of low-skilled jobs (labouring and craftwork) has grown and the number of high-skilled jobs (knowledge work) has grown significantly, the number of middle-skill jobs (generally those that require a full secondary education but little else) has fallen dramatically over the last 27 years.

According to the UK Business Insider, the chart is based on data from MIT economist David Author and shows that while the number of low-skilled jobs (labouring and craftwork) has grown and the number of high-skilled jobs (knowledge work) has grown significantly, the number of middle-skill jobs (generally those that require a full secondary education but little else) has fallen dramatically over the last 27 years.

In other words, the advent and adoption of Internet technologies and the development of heavily customerised user/supplier interfaces has resulted in a hollowing out of the types of jobs that are available in the advanced economies: low-skilled work is available, knowledge work is growing but the number of middle-range jobs is declining dramatically, which is going to put a lot of people out of work. The section of the workforce, those with no more than secondary education and possible years of experience, are suddenly going to find themselves part of the long-term, structurally unemployed. To get back into work, they will either have to downgrade to low-skilled jobs with the associated loss of status and reduced income, or else they will have to return to full-time education to up-skill themselves and obtain advanced knowledge and thus seek employment in the still small but growing knowledge work sector.

I recently came across an example of a governmental department that, at the beginning of the technology change, had 600 employees and now, a few years later, was a highly efficient organisation delivering an increased level of service with a reduced workforce of around 100 – and none of the 500 redundant workers had been able to find a job at a similar level and salary scale as before. Those 500 were now long-term and structurally unemployed, and costing the government in terms of social security.

Essentially, the chart above shows that all the developed economies of Europe, with the addition of the USA, face a long-term trend towards rising structural unemployment, rising demands on the social security/unemployment benefits system, decreased levels of disposable income, decreasing growth, possibly decreasing GDP, increasing levels of poverty and a widening poverty gap. To address this sort of issue will require changes in political policy, but there appears little recognition of the issue at the national political level and certainly no policies are being put forward. Instead, political leaders from the US President, Donald Trump, and the UK’s Brexit-preoccupied PM, Theresa May, to the Commissioners of the European Commission, are all blandly talking about job creation and economic growth. Somebody needs to take action soon!

Let’s be entirely honest here. According to research data, more than 70% of ‘change projects’ and ‘change management projects’ fail to deliver the desired results and often deliver needless disruption and a negative return on investment. Some organisations, however, buck the trend and consistently deliver desired results, often with a much higher return on investment than anticipated. The question we need to ask is: why?

In over twenty-five years as a change management practitioner I have found that the answer to the question “why do most change projects fail?” is (1) organisations try to change the wrong things, (2) they fail to engage their people, and (3) they make changes that are not needed.

Let’s unpack that a little.

Changing the wrong thing

Changing the wrong thing often means that individual processes are being modified without a full understanding of how that process is linked to others in the organisation. When an organisation is regarded as a machine, and this seems the predominant way managers think about organisations in western economic models, then the process mentality comes into play and the inner workings of the machine are set up to work in an interlinked way with the output of one or more processes acting as the input for a subsequent process. If a decision is then made to modify either the input or the output of a process then it has an immediate impact on the process either side and this has a continuing knock-on effect throughout the organisation.

Generally speaking, a process has a very narrow performance band within which it has to operate if it is not to be disruptive and care needs to be taken not to create conditions under which that performance band is breached. So, even undertaking routine software upgrades and replacing old equipment can and do cause disruption, some of which will not have been foreseen or anticipated. If such upgrades are planned, then it is essential that the organisation tracks all the performance line through all the processes to see what else will need changing.

And then, of course, there is the change that is generated by tactical actions taken for the right reason but without the process analysis being done. For example, the sales team are tasked with increasing sales by 10%: this seems like a logical tactical activity but a 10% increase in sales, unless there is an excess of stock, will require a 10% boost in production and all the processes that contribute to that. Such a demand thus requires a significant change in a great many processes, some of which will not kick in until much later and usually lead to a delayed stock increase sometime after the sales boost and this leads to the need for a reduction in performance. Thus the roller-coaster affect kicks in and the ROI boost expected from the sales boost turns into a negative ROI later on.

The golden rule is that as far as possible change should be considered only in long-term strategic situations and avoided in short-term tactical ones.

Not engaging the people

For far too long managers in organisations have held the belief that all they have to do is ‘to issue an order’ to their workforce to do things in a different way and it will happen. But long gone are the days when the relationship between organisation and employee was that of ‘master and slave’ and simply ordering something done was acceptable. In the current western economic model the relationship has shifted significantly towards a mutually beneficial one and full recognition of the portability of skills. In other words, people work for organisations only so long as they wish to and evidence shows that a person leaving an organisation and actively seeking another post will usually find one with better conditions and higher pay within a few months.

When people work for any organisation they are usually employed to undertake some specific duties and some unspecified but related duties, and to do so on a continuing basis. This means that the employee is required to deploy a fairly limited range of behaviours and skills on a long-term basis, and by doing so these become habitual behaviours or habits.

From a behavioural perspective, an organisation can be considered “a collection of habits with a common goal” simply because habits are “a limited set of frequently (or continuously) used behaviours that enable the individual to deliver a steady performance within a bounded environment, usually without a sense of risk”.

Somewhat obviously, if the “common goal” is changed for any reason, then the habits that are deployed to achieve it also have to be changed, and failure to do so will result in regression to the previous performance. In other words, if you want a different outcome then there has to be a change in what you are doing. There is nothing fancy about that, it is not a deep psychological insight, it is simply a self-evident truth and one with which we are all very familiar with. However, despite its obviousness, it is simply ignored by many, especially those seeking change.

Part of the problem is that habits under-pin our “comfort zones” which are defined as “a behavioural state within which a person operates in an anxiety-neutral condition, using a limited set of behaviours to deliver a steady performance, usually without a sense of risk”. Comfort zones are, therefore, a set of habits and an organisation is a set of comfort zones – so, if seeking change in the way people work we need to change people’s behaviours and habits and this requires a significant understanding of the methods that can be used to assist people to discard old habits and adopt new ones. And anyone who has ever tried to break a long-term habit of their own will know just how hard and time consuming that is.

Making changes that are not needed

This is, unfortunately, a rather recent and disturbing trend born, I suspect, of the speed and frequency of changes in market conditions. Faced with changing demands within the market, organisations must obviously make changes so that they and their goods and services remain relevant in the market, and this has led to a tendency towards an almost knee-jerk reaction within the strategic planning section of the organisation. This is not helped by the fact that changes in technologies are taking place with increased speed and frequency and this doesn’t look like changing in the near future – if anything, it may even get faster.

Such is the importance of responding quickly to the disruptive market that exists in the western economic model, strategic management has shifted from being a proactive supply-side activity and become a reactive response to a shift towards demand-side market conditions: organisations are simply responding in desperation to survive, and strategy has become tactical and very short term. Managers are, therefore, having to ‘think on their feet’ rather than having a thought-out plan and this inevitably leads to grabbing at straws as they scramble to stay close to their comfort zones.

The outcome is multiple contemporaneous changes, high levels of stress and anxiety, and the need for agile and flexible responses, often without allowing a change to settle before the next round of changes is demanded. Whilst this sort of thing can be very exciting and even exhilarating to the managers, it leads to huge disruption and loss of performance amongst the transactional workforce and it cannot be recommended for the long term. Whilst not a change management issue, per se, it feeds into change management and creates instability, a lack of continuity, a declining performance, and potential disaster. There needs to be a return to forward planning, an increase of trust in and expenditure on innovation (and subsequent R&D where appropriate), more thinking and less reaction. Unless this happens then the change manager is always going to fail as today’s changes are not allowed to drive performance before they become yesterday’s failures. Clear, stable goals have to exist as a prerequisite for successful change.

Alasdair White has been a professional change management practitioner for 25 years and heads the Business Academie’s Change Management training programme (accredited by AMPG). His Change Management consultancy work work is structured around addressing the issues that lead to setting up successful change programmes whilst the training programme is aimed at providing change management practitioners with the tools, knowledge and understanding needed to lead successful change programmes.